Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL)

Media x Design Lab

Masters of Architecture Studio

Fall 2017, Spring 2018

The study of the city and the design of its buildings is undergoing a revolution: data, data visualization and data analytics, once scarce, have now become ubiquitous from global smart cities to rural areas of developing countries. Open-source mapping, LIDAR, drone photogrammetry, GPS tracking, smart sensors- the list of new sources of urban data goes on and on even without listing the myriad databases and software platforms. Gathering, combining, analyzing and then implementing this data as a design input is a daunting task for contemporary architects that we have pushed to the forefront of the agenda in the EPFL MxD Xixinan studio.

Engaging the fundamental data behind urban problems can make architects leaders in the definition of larger-scale urban agendas instead of the recipients of increasingly closely bounded design problems. We used our studio in Xixinan as an opportunity to explore the implications of this claim. Xixinan, a rural village in Anhui, with its population depleted, seeks to draw back its departed residents and attract new visits from the increasingly prosperous residents on the coastal Chinese megacities. Deliberately we left the project loosely-defined. We set ourselves one major constraint- a priori- whatever was proposed would avoid replacing existing structures or displacing existing inhabitants: therefore, the proposal would be small and light and probably temporary. Program and location within the village was left to the student to determine. Analysis of spatial and social data should permit the student to discover creative solutions to problems that had been previously unnoticed or poorly understood.

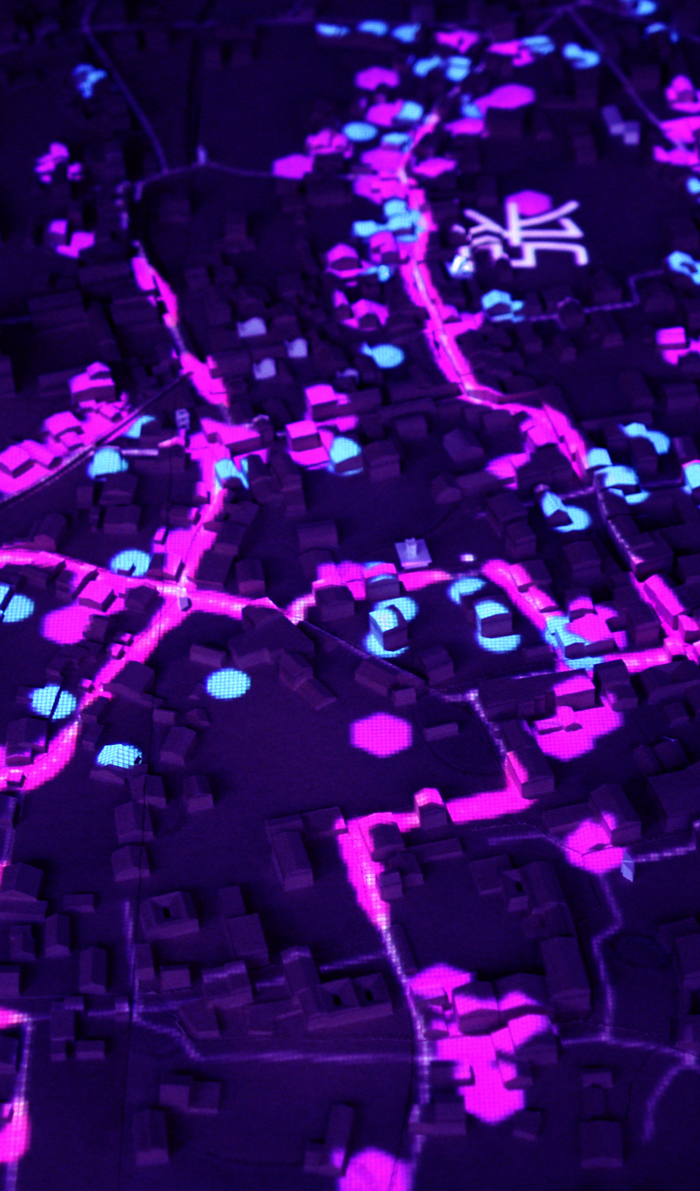

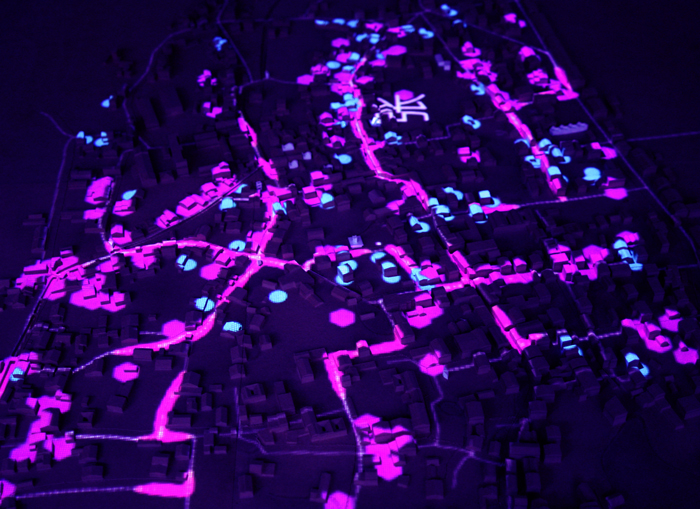

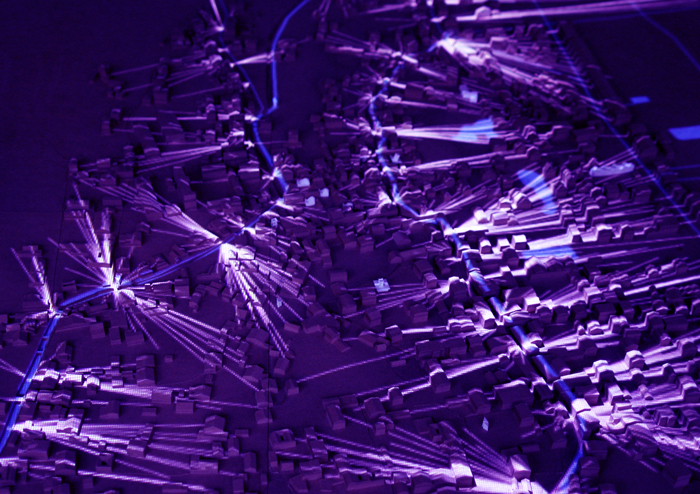

Our analysis of the village- data-intensive- would be the remedy to a persistent doubt: what was to prevent a small intervention from being unseen, unused, irrelevant? The right program at the right spot, we argued, could have social impact much larger than its small size. The village is a framework for movement and an engine of social encounter- analysis of its forms and patterns reveals crucial junctures where people are most likely to pass by, most likely to meet. We identified key paths and intersections through analysis of the village pedestrian network using analytics including space syntax’s ‘integration’ measurement. A database of geo-referenced family names allowed us to overlay hotspots in urban networks with social centralities as defined by family bonds.

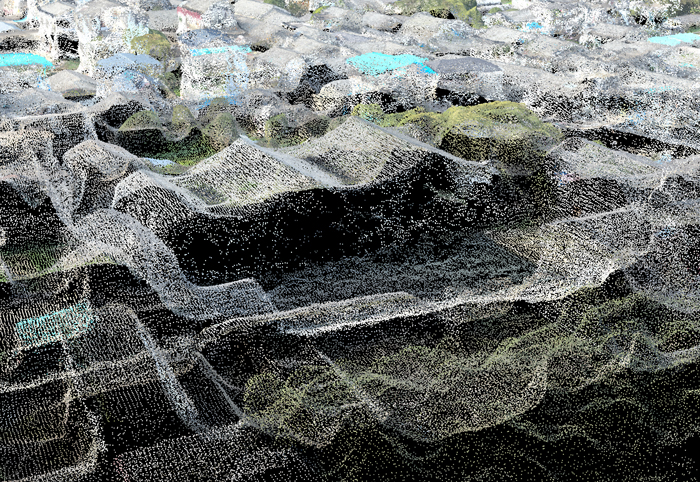

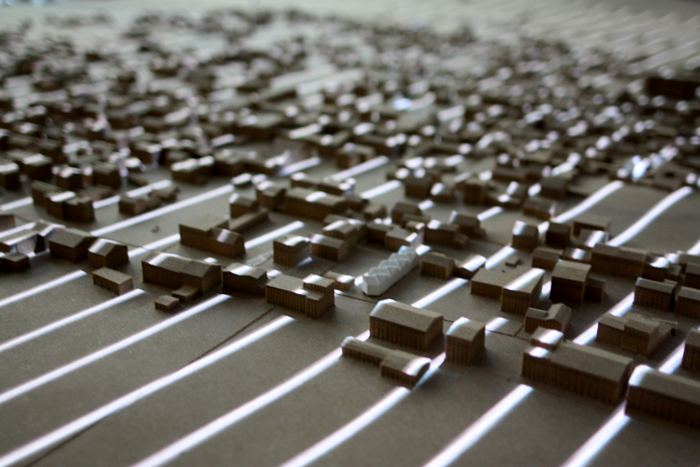

Drone-generated orthophotos and points clouds allowed us to map out patterns of land use, crucial to the economy and social life of the rural village, revealing where land was actively in cultivation and with what intensity. (The drone survey was shared with us by the design collective MAPS and Ignacio Lopez Buson who had conducted an earlier workshop at Xixinan’s Turenscape Academy.) The point cloud also gave us 3-dimensional information on the shape of the historical architecture of the village and the array of small bridges and terraced access points serving its canals. New areas of construction, difficult to identify on the CAD survey but obvious in the drone survey, signaled new intensities of inhabitation. Newly built or widened roads showed us where automobile traffic was infringing on the village fabric.

Building off this analysis students were able to sketch out scenarios of everyday life within the village, using the information drawn from the analysis to make conjectures about who would move where, when and why. We asked the students to consider active interventions in the village’s everyday life based on several verbs – caring, learning, meeting- which encapsulated necessary preconditions to a re-invigorated rural life. Each student examined in depth how architectural affordance might meet the needs of rural activity – caring for the elderly living alone, educating children with absent parents, integrating local patterns of life with temporal swings of a new population of tourists. For each verb we asked students to articulate not only a program fitting these verbs, but also what place in the village would make the biggest difference and specifically what people it would impact. These arguments were articulated in the terms of the data and analysis carried out initially, giving quantitative support to proposals that were ultimately social and architectonic in nature.